Thursday, 15 August 2013

Monday, 12 August 2013

Mamie's Letter - Page 3

In case you missed them, here are pages 1 and 2.

Mamie kept chickens on Sheridan Street apparently. When did it become a by-law that people couldn't keep chickens within the city? If it's not a by-law, I want to start keeping chickens!

We also found it interesting that Joe had never heard the name "Amy" before.

Stay tuned for page 4 on Thursday!

Friday, 9 August 2013

Mamie's Letter - Page 2

Last week we posted the first page of a charming letter written to a young Miss Mamie Woodard from a lad named Joe Ion. This is the second page of the letter, which details Joe's futile attempts at farming, his concern with what Mamie thinks of him, and possibly a bit of jealousy at Mamie's being able to go to the commons with other little friends.

What do you think of this line: "Say, the next time I ask you to go to the show with me, I expect you to go and not say you can't". Way to be bossy, Joe!

Watch out for pages 3 and 4 next week, which will be posted on Monday and Thursday!

Friday, 2 August 2013

Paris, Ont. Aug. 1921

Dear Mamie...

This letter was written in the summer of 1921 by a young man called Joe to a girl named Mamie. Research shows that Mamie would have been about 15 years old at the time, and was living on Sheridan Street in Brantford. Joe was visiting Paris, Ontario over the summer, possibly to visit family and to go camping with his friends; the lad appears to be the same age as Miss Mamie.

Check back next week when we'll be posting Page 2!

Thursday, 1 August 2013

Dear Mamie...

|

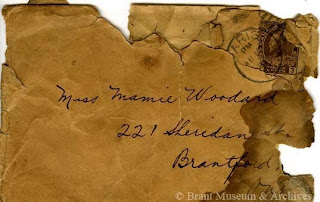

| Envelope, in poor condition, dated 1921 |

Imagine if an email or text message of yours could end up in a museum 90 years from now. What would researchers find? What sort of little things do you mention to friends on a daily basis? If my text messages from this past week were to be uncovered, people would see quick messages from my mum before she caught a flight home, giving directions to a colleague, and texting a friend back and forth about getting together to make peach jam (it's canning season, after all).

But digital communication is so ephemeral. What will future generations know about us and how we communicated? We (most of us anyways) don't print off our text messages. What clues will future people have when they are conducting their own research? We're fortunate to have letters, a form of communication which has mostly fallen by the wayside excepting for business and sometimes legal reasons. Letters are lovely. They are solid, physical pieces that can be examined for the kinds of clues and hints that researchers love.

This letter, addressed to Miss Mamie Woodard and dated summer 1921, was one of the very first things I catalogued when I started working at the Brant Museum & Archives as a summer student a few years back. I was so charmed by the little note (which is in fact several pages long) I spent some extra time researching the details and carefully scanning the pieces for our digital database.

Check into the BHS blog every week: we'll be releasing new pages of this letter in a 6-part series along with transcriptions and research notes.

In the meantime, do the future a favour: send a couple letters, and maybe keep a few of the letters and cards you receive for later generations. And for goodness sakes, put a date on them!

- Carlie

Tuesday, 11 December 2012

Status of Wealth in 19th Century Homes

Myrtleville House is not the typical

19th Century home. The Good’s built a Georgian Style Home, complete

with 10 rooms and 7 fireplaces. The cost to build Myrtleville was

four hundred and sixty seven pounds, five shillings and nine pence

half penny, which is equal to about sixteen thousand dollars today.

When pioneers traveled to the new world they would build a log

cabin, due to their budget and time restraints, so to find a home of

this size and grandeur, it's evident that the Good family was quite

well off.

While touring an 1800s home, there are

several signs of wealth you can keep an eye out for, such as:

Painted floor boards-a luxury that

added beautification to a home.

A multitude of windows, doors , and

rooms in the home- People were taxed on the number of rooms, doors,

and windows in the home. As a result, many 19th century homes did not

have closets. Closets were considered a room, so to cut back on the

cost they would use wardrobes.

More than one story- usually homes in

this time period were built as a half story. From the outside,

Myrtleville House appears as if a single story; however, it is

really two.

Tall white sugar cone. The larger the

sugar cone the wealthier you were. A sugar cone cost $100 in 1811.

They would place their white sugar cone on the window sill to show

neighbours how wealthy they were.

Tea Chest – Tea was very expensive,

and therefore enjoyed only by the wealthy.

Come

visit Myrtleville House, and see how many of these signs of wealth

you can discover!

Friday, 9 November 2012

Chair of the Valkyries

Working in a

museum isn't all lace doilies and petticoats. Some artifacts found

in the storage areas of the museum can be described as unsettling,

disturbing, or just plain scary. Generally speaking, I've gotten

used to some of the less quaint artifacts that the museum houses, but

every now and again I’ll find an artifact that makes me nervous.

For example, this chair. This chair

makes me nervous. It’s found a home in a storage room and has been

there for quite some time, but it still surprises me every time I

open the door. Staff members have taken to giving the object pet

names such as “Satan’s Chair”, “Demon Chair”, “Loki’s

Chair” and “Seat of the Damned”.

Part of our collective discomfort may

stem from the fact that we know so little about the chair. It was

donated in 1962, and was described as being “many years old”,

which though true is peevishly vague. The piece is crafted out of

black-lined brown leather which is button-tucked in places, and pairs

of animal horns styled around the edges. Even the feet of the chair

are embellished with horns, though supported with cylindrical brace

bars. The estimate is that this chair is probably from the early to

mid-1800s, and it’s my personal guess that it belonged in a

gentleman’s office, billiard room, or hunting cottage, simply

because no Victorian lady of taste would possibly have let this

object into their parlor or salon.

Part of our collective discomfort may

stem from the fact that we know so little about the chair. It was

donated in 1962, and was described as being “many years old”,

which though true is peevishly vague. The piece is crafted out of

black-lined brown leather which is button-tucked in places, and pairs

of animal horns styled around the edges. Even the feet of the chair

are embellished with horns, though supported with cylindrical brace

bars. The estimate is that this chair is probably from the early to

mid-1800s, and it’s my personal guess that it belonged in a

gentleman’s office, billiard room, or hunting cottage, simply

because no Victorian lady of taste would possibly have let this

object into their parlor or salon.

The research for this piece suggests

that the horns are from buffalo, but pieces of horned furniture,

which were popular throughout Europe and North America in the 19th

century, could be crafted with the horns of any animal, including

elk, moose, and even cattle. Its provenance is likely similar to a

mounted moose head or bear skin rug, as generally, items like horns

and animal skins were used as trophies as signifiers of a successful

hunting trip.

The chair lives in

an upstairs storage room. I've taken to calling it the Chair of the

Valkyries, because it reminds me of the typical depiction of an opera

singer with a horned helmet, especially typical of Wagner’s opera

Die Walküre, specifically the third act’s “Ride of

the Valkyries”. Also, Elmer Fudd in the Looney Tunes cartoon

“What’s Opera, Doc?” who sings “kill de wabbit!” to the

tune of Wagner’s most recognizable piece.

The chair lives in

an upstairs storage room. I've taken to calling it the Chair of the

Valkyries, because it reminds me of the typical depiction of an opera

singer with a horned helmet, especially typical of Wagner’s opera

Die Walküre, specifically the third act’s “Ride of

the Valkyries”. Also, Elmer Fudd in the Looney Tunes cartoon

“What’s Opera, Doc?” who sings “kill de wabbit!” to the

tune of Wagner’s most recognizable piece.

So the chair doesn't belong to a

villainous demon, plotting anti-hero, or a mythic Norse soprano, and

instead likely originated from the private quarters of a wealthy

Victorian gentleman with a penchant for hunting. It still creeps me

out.

Carlie M.

Program Coordinator, Brant Museum and

Archives

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)